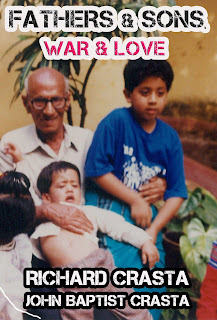

Biography of John Baptist Crasta, oldest first time Indian author

SJohn Baptist Crasta, 1910-1999, is the father of Richard Crasta, the author of eight books. He was born in Kinnigoli, and walked barefoot for 20 miles through tiger-infested jungles to join his high school in Mangalore. Miraculously escaping an earthquake at Quetta, he joined the British Indian Army, and was captured by the Japanese. His memoir of being a Prisoner-of-War of the Japanese during World War II was published by his son, who edited the book and added an introduction and three essays to it. The book was originally launched on December 27, 1997, and later in 1999 (second edition), is now published in a new edition on Smashwords and at Amazon.

At the time that it happened, John Baptist Crasta was the oldest Indian to have his first book published: he was 87 years old when it happened, and the manuscript had lain in his steel trunk for 51 years after he wrote it.

At the time that it happened, John Baptist Crasta was the oldest Indian to have his first book published: he was 87 years old when it happened, and the manuscript had lain in his steel trunk for 51 years after he wrote it.

And this is the short biographical introduction that appears in EATEN BY THE JAPANESE: THE MEMOIR OF AN UNKNOWN INDIAN PRISONER OF WAR:

But we mustn’t go too far back, must we, we mustn’t go too far back in anybody’s life. Particularly when they’re poor.—Martin Amis, London Fields.

My father, John Baptist Crasta, was born on 31 March 1910, in Kinnigoli, India—a remarkable achievement, because nothing has, does, or ever will happen in Kinnigoli. Luckily for it, the village has a road connecting it to the larger port-town of Mangalore, in the monsoon-drenched Southwestern pocket of India where little of earth-shaking importance has happened since the beginning of time, and where in the first half of this century, tigers still roamed the surrounding villages and occasionally strayed into town, snacking on domestic animals and people, once biting off the fingers of a man preoccupied with answering the call of nature in an outhouse at night. My father was the firstborn of eight children, the others being Lucy, Antony, Aloysius or Louis, Ignatius, Bonaventure or Bonu, Margaret, and Gerald. Make that eight thin children. “We came from a family of thin people,” said Uncle Louis recently, himself pretty thin despite ascending in mid-career to the world of medium-fat cats.

The Crasta children may have been thin in body, but their lives were thick with rosaries. “No rosary, no rice,” was their mother’s domestic diktat. Religious piety was a staple among these Konkani-speaking descendants of converted Catholics, refugees from the Portuguese Inquisition in Goa of the late seventeenth century, and survivors of Tipu Sultan’s persecutions over a century later. In this verdant corner of a country where life was nasty, brutish, and often cut short by snake bites and other arbitrary acts of nature, religion possessed an awesome power over its trembling adherents.

His own father, Alex Dominic Crasta, was often absent from his life, working and living an inaccessible seventy miles from home in the mountainous jungles of the Western Ghats. “At one time, he owned four or five gadangs [toddy shops],” Uncle Louis remembers. In my father’s fuzzier memory, it is his mother who gets the credit for shaping his childhood. “My mother, my saviour,” he characterized her recently in a quavering voice while gazing at her photograph, tears welling up his eyes.

Her name was Nathalia, and she was both a housewife and a provider. She would feed all her children first, and then eat the leftovers, if any (a not uncommon habit among Indian mothers; my mother often did likewise). One day, as she was massaging Baby Louis according to local custom, her two-year-old second son, Antony, had toddled off into an open well and drowned, despite her jumping in after him to save him. Later, still another son, Ignatius, succumbed to the bite of a rabid dog, there being no effective medicine for rabies at that time, at least none accessible to the indigent citizens of Kinnigoli.

“They took me away and didn’t let me see the body,” Uncle Bonu recalled later. “But I could hear them weeping loudly, inconsolably. Then they killed the dog.”

“He was sado—simple and straight, never talked ill of anybody, never got into fights,” my uncle Louis says of my father. When it came time to enter high school, my father walked the wooded and hilly twenty miles to Mangalore and lived there as a private boarder while attending Saint Aloysius High School. One day, when his mother heard that he was sick, she, being too poor to afford the bus fare, carried Baby Gerald on her arm and walked the twenty miles to Mangalore to see him.

It is harder for a rich man to enter Heaven than for a camel to enter the eye of a needle, or so the Bible says; but it was always pretty easy for a rich man to enter St. Aloysius College and its high school, and to escape the whipping the padres gave to the fiscally and morally unlucky. After all, the college towered over property donated by the local squire, its chapel being a magnet, every Sunday, for the town's cream of Catholic society. My father, though not one of India’s wretched poor, was consigned by his family income to its struggling lower middle class. And often, because he had not paid his two-rupee monthly school fees on time, he was kicked out of his St. Aloysius High School classes by the Italian Jesuits who were then in charge.

Thanks to a last-minute loan, my father paid his exam fees and obtained his high school diploma. Mangalore still being a one-hundred-bullock-cart, fifteen-horse-carriage, seven-Model-T-Ford town with limited employment opportunities, most local high school graduates would head for the nearest metropolis, Bombay, to find a job. Thanks to the invitation of a family friend, Ignatius, my father hopped on to Karachi instead. After five years of assorted labor in Karachi, he joined the Army in 1933.

The next year, he learned of the death of his father. On Easter Sunday, 1934, my grandfather caught pneumonia, and it was decided to take him to the nearest hospital in Mangalore twenty miles away. The mode of transportation? The bullock cart of a friend. However, the cart’s owner did the Christian or Mangalorean Catholic thing: he decided not to miss his Easter revels of booze and delicious pork and mutton curries. Festive meals, which occurred about four or five times a year at Christmas, Easter, the parish feast, and wedding celebrations, were not to be sneezed at in those lean times. It was nightfall before the cart started for Mangalore with its human cargo. When it reached Father Muller’s Hospital the next morning, Dr. L.P. Fernandes lifted the sheet, checked my grandfather’s pulse, and said, “There’s no point admitting him. He is dead.” My grandfather’s body, having joined The Dead shortly after the time that his friend celebrated Jesus Christ’s rising from it, was upgraded to taxi class on the return trip to his Kinnigoli graveyard.

Did this perfectly silly end to my grandfather’s life make my father resolve that he would not easily become Death’s victim? Possibly, for he narrowly escaped a devastating earthquake that struck Quetta the following year. And then, six years later, he found himself in a war, but survived, against all odds, to write this memoir, and kept it safe for 51 years through dozens of transfers until his son, by then a published author, discovered it and published it himself..

At this point I will let my father, first published at the age of 87 3/4 in a limited edition sold only in his home town, take over the narrative.

Comments